THE GREY FOLDER PROJECT

Glimpses of a Lost Life:

Essay by Toby Sonneman in Der Letzte Sommer/ The Last Summer

Photos by Eric Sonneman

AS I WAS GROWING UP, my father often told me stories about how and why he left Nazi Germany in December of 1938 and came to America. My father had planned to become a pharmacist, but his training was interrupted by Nazi policies. By 1935, when he was in his mid-twenties, he had lost two jobs in Mannheim due to ‘Aryanization,’ as Jewish business owners, suffering from boycotts and discrimination, were pressured to sell their businesses to non-Jewish owners for a mere pittance of their value. Jewish employees were dismissed. Jews were banned from parks, restaurants and swimming pools. A boyhood friend who had joined the National Socialist party took my father to hear Hitler speak. He was horrified. “Erich, you’d better get out of Germany,” the friend warned him. “We’re going to bury the Jews.”

In spite of all this, before Kristallnacht—the violent pogrom in November of 1938 that marked the beginning of the Holocaust—many aspects of life seemed relatively intact. My father still led a Jewish youth group and had a permit to take groups around Germany to visit places such as the Gothic cathedral in Köln. He collected unemployment insurance even though his lack of work was clearly related to Nazi discriminatory policies.

“Until Kristallnacht, life went on more or less as before,” said Suse Underwood, a relative from Heilbronn who was 12 when she was sent on the Kindertransport, Britain’s program to rescue Jewish children from Nazi Europe, shortly after Kristallnacht. “Occasionally one heard of some unpleasantness or somebody ending in Dachau or another KZ, but the major unpleasantness only touched us all in November, 1938, with the burning of the synagogues.”

AS MY FATHER PHOTOGRAPHED DAILY LIFE in 1937 and 1938, he was also—perhaps unknowingly—documenting a world that was about to be eradicated. Still, the photos showed a life that seems, from the perspective of today, disconcertingly pleasant. A holiday in Italy to visit an uncle. His father’s hands on the piano in the living room, his mother and her sister sitting in wicker chairs on the leafy balcony of their Mannheim apartment. A gathering of the family—my father, his brother, their parents and aunt Frieda who lived with them—at a table set with wine glasses, framed art and photographs on the wall behind them. My father took this last photograph in the apartment where they’d lived for 22 years, so it must have been before September of 1938 when they had to move, probably due to economic pressures.

In one striking photo, my father’s mother, Berta, walks with her sister Frieda down the street near the apartment, both dressed in fashionable dresses and jaunty hats. When I look at that photo I think of what was to follow –- my grandparents making a last minute escape from Germany and traveling through Siberia and Asia to reach the United States; Frieda arrested and deported to a concentration camp in Vichy France and then to Auschwitz where she was killed.

MY FATHER PHOTOGRAPHED the people and farming life of Freudental with special affection. His mother had grown up in this village, and her brother Moritz Herrmann remained there, buying land and becoming a first-generation farmer. From his childhood, my father loved to spend summers in Freudental, helping on the farm, sharing the home with Moritz, his wife Sidonie and their son, Adolf.

The long summer days in Freudental held a full sunrise-to-sunset routine. Moritz wakened the farmhands, including my father, at 3:30 in the morning. “We had but a glass of milk, harnessed the cows to the wagon, and by approximately 4:30 were at his land, plowing the earth, spreading seeds by hand or harvesting the hay or wheat to be threshed later on.”

They returned home about 8 a.m. for a full breakfast to sustain them for the rest of the workday. “After breakfast, clean and milk the cows. We searched for eggs, and off we went to the fields for continuing work until the sun set,” my father recalled. With only two breaks in the hours that followed—for lunch and a short afternoon nap— they returned home “dead tired,” then cleaned the animals, milked them and fed them hay and water. “Then we had supper with Moritz giving the blessing, Sidonie and the women helpers serving. Finally, up to bed. . . And there was Moritz, at the door, “’Get up, get up – another day is here!’”

The harvest of wheat or hay, as depicted in the Freudental photos, occupied most of the day’s labor. With the exception of the threshing machine, which was hired communally by all the farmers in the village, all the work was done by farmhands and animals, my father recalled.

On Fridays, my father was given a special job: the bakery route. He learned how to harness the two oxen to a cart, then helped his aunt Sidonie load the cart with wooden boards full of unbaked cakes and loaves of Berches, the braided Sabbath bread. He slowly drove the cart to the village bakery ovens in the morning, and returned in the mid-afternoon to load all the freshly baked goods onto the cart and return home.

“Oh, yes, in your spare time,” my father said, “keep looking for and gathering eggs!”

Besides running his own farm, Moritz also trained young people who wanted to immigrate to Israel, preparing them for work on a kibbutz or a community farm. Yet he himself was not a Zionist, my father said. “He had absolutely no wish to emigrate,” he said. “He loved his work and the land.”

We know that my father made these photographs of the harvest in Freudental in the summer of 1938—mere months before Kristallnacht and before his departure from Germany in mid-December of that year. But long before he took these photographs, he had decided to leave Germany.

“I WAS FULLY AWARE of what could happen to us,” my father told me, though many other people “still had hopes that all was going to pass.” He wanted to go to America, but an applicant for a U.S. visa needed an affidavit of support, usually from a wealthy American relative who would promise to financially support the immigrant should he or she not find employment. This requirement, often harshly interpreted, meant that American quotas for German immigrants were never filled, despite the large numbers of German Jews who wished to emigrate.

For my father and his family, this stipulation seemed impossible. An affluent American relative? They agonized, trying to come up with a name, an American relation—but could think of no one.

Then, as if in a fairy tale, my father’s mother awoke one morning having dreamed of an American woman who’d visited her family many years before. After a query to a cousin, they learned that the relative was a distant and wealthy relative, Emma Loveman from Nashville, Tennessee. My father wrote to her immediately asking for help, and without any further queries, Mrs. Loveman sent an affidavit of support, the very paper that my father needed for his application. He added it to the stack of required documents—from school certificates and certificate of health to employer recommendations and certificates of good conduct, as well as notarized translations of documents into English—and applied for his visa. It was probably 1937 when he applied and it would be a year before his number came up. The appointment with the American Consulate in Stuttgart was set— for November 10, 1938. The morning after Kristallnacht.

%20on%20the%20cart%2C%20Freudental%20.jpg)

AROUND THIS TIME of mixed hope, anxiety and waiting, my father was also taking photographs, documenting a variety of subjects. To be sure, he took many personal photos of family and friends at the table, on a picnic or hiking, but the photo collection also reveals my father’s strong interest in work. There are photos of welders, woodworkers and wallpaper hangers; office workers and sign makers. There are cooks in a commercial kitchen, nurses in a hospital. His photos of the harvest in Freudental combined these two threads, as they showed family and friends in this close-knit community working together in the harvest.

My father probably acquired the camera he used for these photos after June, 1936, when he began working as a lab assistant for Gamber Diehl, a photography lab in Heidelberg. (A Jewish aid agency found him the job when Gamber Diehl was still run by a Jewish proprietor. The business was later Aryanized, in 1938.) The camera was a Rolleiflex, a high-end twin-lens reflex camera made in Germany, a favorite of professional photographers after it was introduced in the late 1920s.

Valued for its precision build and superior optics, the Rolleiflex offered photographers a large and precise viewfinder. The twin-lens reflex camera, which is held at chest level while the photographer looks down at the viewfinder, was less obvious and obtrusive than the 35 millimeter camera. Further, the 6 cm. x 6 cm. square negatives of the Rollei were roughly three times bigger than those of 35 mm. film, which meant they could be viewed as contact prints, without being enlarged.

The sharp, clear images of my father’s photographs were no doubt the result of both the high-quality camera and the skills he learned working at the photography lab. “Mr. Sonnemann has been involved in all the branches of our Laboratory for photo-work such as developing, copying, enlarging and retouching,” reported a testimonial from Gamber Diehl dated May 21, 1937. “Mr. Sonnemann is diligent and he has performed the work. . . in a careful manner and to our entire satisfaction.” This certificate attesting to my father’s technical skills was submitted in his visa application and may have helped my father’s chances as the U.S. Consulate moved with painstaking slowness through thousands of applicants.

ON NOVEMBER 9, 1938, the friend who had joined the Nazi Party warned my father and his family that pogroms against the Jews were planned throughout Germany that very night. The family hid in the attic, nearly paralyzed with fear as they heard the chaos of shouting, the crash of breaking glass from the windows of storefronts. Furniture was thrown from windows and balconies to the street. It was Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, and Nazi storm troopers burned synagogues across Germany and Austria, trashed and looted Jewish homes and businesses, and sent some 30,000 men to concentration camps. All illusions that Jews could live freely in Germany collapsed in one shockingly violent explosion.

In Heilbronn, Suse Underwood, then 12, met a classmate who told her “’The synagogue is BURNING!’

“I was reluctant to believe her and said I would go and see for myself,” she recalled. Joining a crowd of spectators, she saw the flames enveloping the synagogue and noticed four members of the fire brigade directing their hoses, “one on each side of the synagogue, precautionary or even for show, rather than to extinguish any flames.”

She walked on to her school. “An image which has imprinted itself on my mind,” she said, “is of my teacher as if turned to stone, standing at the window and watching the flames.”

Nearby in Freudental, the planned violence began the next day, as Nazis from Ludwigsburg joined local Nazis to demolish the interior of the synagogue—it was not burned only because a fire in the center of the village would have caused too much damage to surrounding buildings. Prayer books, Torah scrolls and benches were thrown out of the synagogue, taken to the soccer field and set on fire, while the Jewish men and boys were forced to kneel around the fire and chant, “We will leave the country, we will go.” Later the men and boys were taken to the town hall where they were beaten and made to declare that they were “pigs,” while the Jewish women were forced to clean the courtyard and street in front of the synagogue.

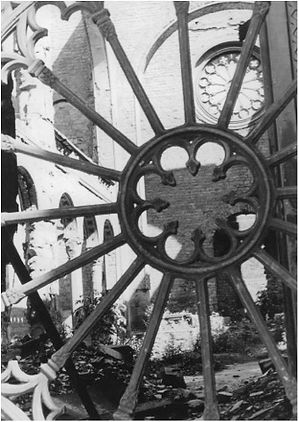

IN MANNHEIM, THE CARNAGE began in the early hours of November 10, as storm troopers forced entry into the main synagogue and used explosives to set the building aflame. One tried to shoot down a chandelier. “I saw the glee in the faces of the German onlookers,” remembered one Jewish eyewitness, “and the Fire Service that stood by to protect the neighboring properties but made no attempt to douse the flames.” The roof of the synagogue collapsed in the flames. Later, the Nazis returned to smash any items that did not burn and to steal silver or other valuables.

Only hours later on that morning of November 10, my father had to keep his long-awaited visa appointment with the U.S. Consulate in Stuttgart, about 60 miles away. On his way to the train station, where he would take a slow train so as to be less conspicuous, he walked alone on streets littered with shards of glass and smoldering rubble, past the destroyed synagogue with its smashed windows, charred Torahs and prayer books. He stopped only to rescue one still-intact Torah and hide it among the ruins.

The American Consulate in Stuttgart was ominously silent. Usually, in 1938, the building was crammed with applicants, a line flowing from the second-floor offices to the street and circling around two blocks. On this day, in stark contrast, my father saw nobody but two SS men guarding the door. Bravely, he strode past them.

My father did not get a U.S. visa that day. A physical examination determined that he needed a hernia operation, and he went straight from the consulate to the hospital. But six weeks later, his visa was granted. He said goodbye to his family—hoping that their visa applications would also be successful—and left Germany on December 13, 1938. When he boarded the ship for America, he took with him a simple cardboard box, in which he’d organized his photo negatives by general subject headings. The little squares of black-and-white film remained in the dark recesses of this box, unseen, for nearly 80 years.

FOR MORE THAN FIVE YEARS, in an effort to understand more about my family’s past in Nazi Germany, I had been examining documents that my father left behind after his death and discovering more through the resources of the Mannheim city archive, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the International Tracing Service and various other archives in Germany, France and the United States. At this point, I was sure there was nothing more to discover.

I was wrong. Another discovery awaited me in my own home, and like the cliché, it was hidden in plain sight. I found it inadvertently, searching my closet for a scarf that I wanted to bring with me on my trip to Germany in October of 2017. On a high shelf of the closet, where I kept a small stash of silk scarves, I spotted an old cardboard box labeled, in my father's distinctive handwriting, "Negatives, Europe."

I had known about the box since I'd brought it back with me from Chicago after my father's death, thirteen years before, but I'd never figured out what to do with it, other than save it. I didn't have a way to view the negatives and had little idea what they portrayed. So I’d tucked it away in the closet and had nearly forgotten it.

Now, as I took a fresh look at the paper folders that held groups of negatives inside the box, I recognized in my father's hand the words on a few of the files: "Landscapes," "Freudental," and "Portraits." I held some of the photos up to the light, and saw scenes of farming, of hands on a piano, of street signs surrounded by Nazi flags. All these photographs, I realized, must have been taken before my father left Germany at the end of 1938.

Although it was difficult to make out the images—and I felt overwhelmed by the hundreds of negatives—I suddenly realized that the re-discovery of the box of negatives had come at the perfect time. On my first stop in Germany, I planned to meet with Karen Strobel, at the Mannheim City Archive. Would the Stadtarchiv be interested in archiving these negatives? I asked her. Not only was the answer a resounding yes, but the archive also offered to digitize the negatives for me and other historians and researchers to use.

As the negatives were digitized and turned into positives, fascinating images began to appear as if emerging from a dense fog. The images were clear and crisp, a lens to the past. When I visited Freudental that same autumn, I showed the first images to Steffen Pross, a journalist in nearby Ludwigsburg, as well as historian and author who has chronicled the Jewish past of Freudental. He told me later that he was stunned by the photographs. “The pictures for me are a sensation,” he said. “They are a treasure, because they make so many aspects visible that we knew, but never had seen before.”

Thus the idea for an exhibition and catalogue of the photographs was born. It became a reality with the vital support of the Pädagogisch-Kulturelles Centrum (PKC) of Freudental, a remarkable organization that restored the former synagogue (no longer a place of worship after November, 1938, it was threatened with demolition in 1979), and transformed it into an educational and cultural center, “a house of remembrance and of learning, a place of conscience, dialogue and meeting.”

WHEN I HAD BEGUN intensively researching my family’s history in the Nazi period I had only one photograph of Frieda Berger—my grandmother’s sister who did not get a U.S. visa in time to save her. She was deported from Mannheim to the concentration camp in Gurs, France, in 1940, and to a gas chamber at Auschwitz in 1942. I felt a special connection to her because my parents had given me the affectionate diminutive of her name, Friedl, as my middle name. But in five years of research, I had found only one more image of her. Now, with the digital copies of my father's photographs, there were a dozen or more. They showed Frieda in the apartment that she shared with my grandparents and family, Frieda reading a newspaper, Frieda walking on the street with her sister Berta (my Oma), Frieda at the table with my father's family. Looking at those photos, I could finally imagine her as more than just a victim of the Nazis; rather, as a complex person in her own right.

There were photos of other members of my family and their friends too, some who survived, many who did not. Clearly, one can see that these days before Kristallnacht were happier times, even as one knows now that the times were also fraught with dark omens.

Of the Freudental photos, I feel a particular connection and bittersweet emotion. I recall my father’s fond description of the long days spent working on his uncle’s farm before it was stolen by the Nazis; I see and sense the warmth and intimacy in the gatherings of relatives and friends who never imagined what was to happen to them; I recognize the familiar faces of those who would be murdered in the years to come, including Moritz and Sidonie Herrmann and their teenage son Adolf.

From that tangled history, these photographs draw both their poignancy and their power.

NOTES: All quotes by my father were taken from interviews or letters. The description of the typical day at work in Freudental was part of a letter to Miriam Wittner (with a copy sent to me) written by my father in 2003. Statements by Suse Underwood were quoted from e-mail interviews in June and July, 2018. Details of Kristallnacht in Freudental were given to me by Steffen Pross. Descriptions of Kristallnacht in Mannheim are by Walter Bingham, Reminiscences of Kristallnacht in the Jerusalem Post, Nov. 10, 2014 and by Volker Keller in Judisches Leben in Mannheim, p. 31, as cited by Karen Strobel.