THE GREY FOLDER PROJECT

The Grey Folder

1. An introduction

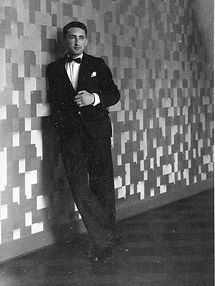

HE GREY FOLDER entered my life one day in November of 2004, some five months after my father had died and my mother had moved to a retirement home. My partner Steve and I were in the basement of the red brick bungalow on the South Side of Chicago where my parents had lived for 52 years (and where my siblings and I grew up), sorting through literally thousands of items. Nearly every object held a memory and each required a decision: keep, donate or throw away. I had to be quick and decisive if this task were ever to be complete.

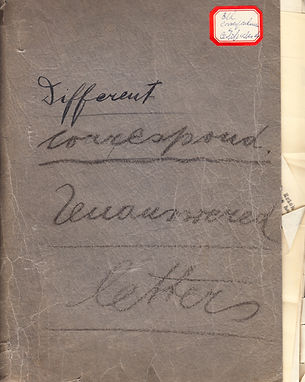

Sandwiched between boxes of old stationery from my father’s chemical business, the grey folder did not at first seem noteworthy. It was plain, a paper binder the color of elephant skin, with metal prongs to hold loose papers. The words “Different /correspond./ Unanswered letters" were scrawled across the front in black crayon, in a handwriting I did not recognize. At the top corner, my father’s slanting handwriting also vaguely described the contents on a label: “Old correspondence and certificates.”

T

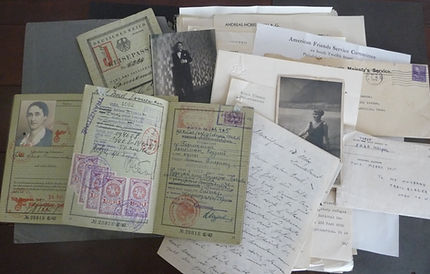

I GAVE THE GREY FOLDER only a brief glance, just long enough to see swastikas on some of the yellowed pages, and note official looking letters from varied governments, dated from the late 1930s. Many of the letters and documents were in German, which I couldn’t read, but they seemed to be related to my father’s escape from Nazi Germany.

“Keep it,” I said, as I handed the folder to Steve.

Even though I was done writing about the Holocaust (I then thought) I might someday donate the materials to an archive. The grey folder was transferred to a small pile of documents to be stashed in a closet drawer in my mother’s two-room apartment.

Then I forgot all about it.

SEVEN YEARS LATER, another death—my mother’s—meant another sorting and sifting of possessions. This time I looked more closely at the grey folder and the letters it contained. They were from various countries—Britain, Sweden, Denmark, Mexico, Canada, The Netherlands. Each had to do with visa applications. And each was a rejection.

“Look at this one,” I said to Steve, who was once again helping me sort through the detritus of my family history. “’The Royal Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs has the Honour to inform you herewith that your application for a Swedish visa has been refused,’” I read aloud. “The honor! How dreadful.”

The letter, dated October 27, 1939, was addressed to my father in the U.S., where he had immigrated just months before, a response to his request for a visa for his parents.

I was intrigued—but once again, I had little time and even less space for the boxes of papers I wanted to keep. And so the folder was shunted away, packed into a UPS box along with some photo albums, and relegated to a space in the corner of a cramped storage unit. Two more years passed before I brought the box out of storage and took the grey folder to my desk.

At last—nine years after I first laid eyes upon it—I was ready to study the folder’s letters and documents in earnest. They fell into two main groups, I found. One group consisted of the extensive documents and certified English translations of the documents required for my father’s application for a U.S. visa. The other group contained the letters from various governments, rejecting my father’s urgent request for help for his parents as they waited in Mannheim, Germany, in 1939 and 1940, for a visa to the United States.

A sampling of the contents of the grey folder

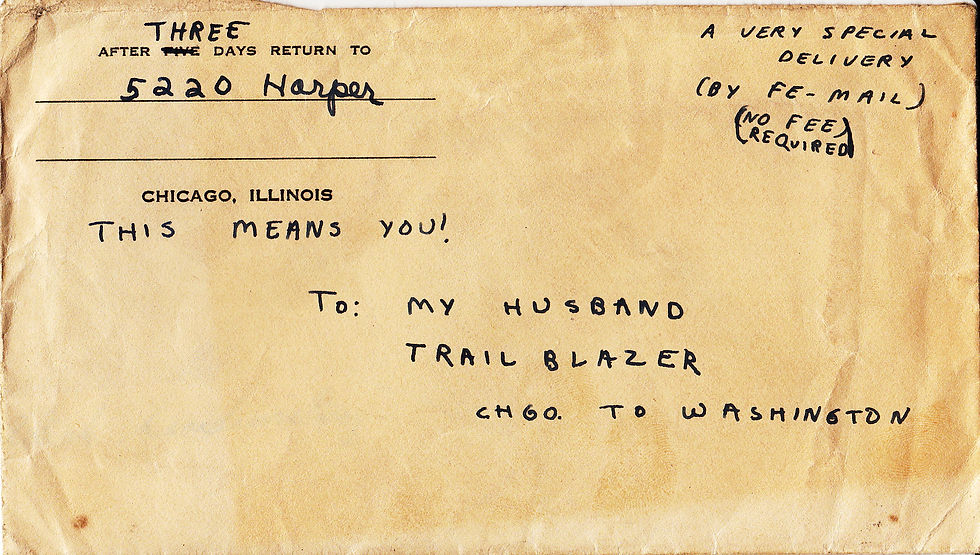

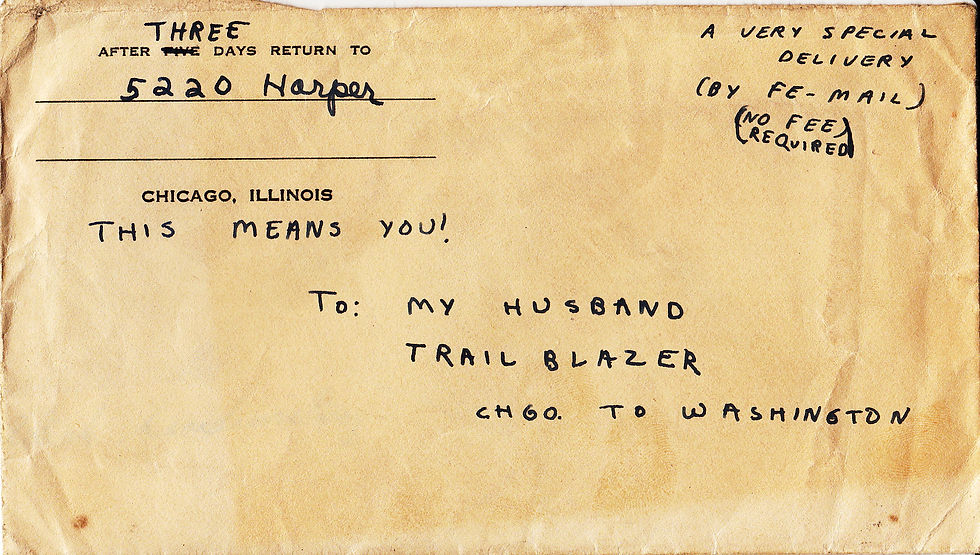

AND THERE WAS MORE. Hidden between the pieces of bound paper, I discovered two envelopes I hadn’t seen before--one containing a letter to my father from his family, written when he was crossing the Atlantic to America in March of 1939; the other a letter my mother gave to my father in 1942 as he boarded a train from Chicago to Washington D.C. for an appointment with the State Department, to plead for a visa to save the life of his aunt Frieda, interned in Vichy France.

As the grey folder began to reveal its secrets, it also stirred up new questions and mysteries. How had my grandparents survived in such treacherous times, especially after Germany had invaded Poland and the war had started? Why hadn’t the State Department helped my father and grandparents to rescue Frieda? Why did France imprison Frieda and others of my family’s relatives, and why did French officials help deport them to Nazi death camps in Poland? And what had happened to my mother’s relatives from the area that was by turn Russia, Poland or Ukraine, the relatives I knew of only vaguely as “victims of the Holocaust”?

I had thought that I already knew about my family’s Holocaust history. I was finding out that I did not.

THUS BEGAN A SEARCH that I came to call my “Grey Folder Project” even as the research led me past the contents of the folder. I followed clues, carried on extensive conversations with archivists and historians over years, pored over obscure documents from archives in Germany, France and the United States, looked for information in Israel and the Ukraine. I traveled to archives and memorials, to internment camps and streets long-ago inhabited by my relatives in Paris and the French Pyrenees, in Mannheim, Munich and other towns in Germany, in search of memories and details, remnants and remembrance.

In short, I found the Grey Folder Project so compelling that I gave myself over to it, not knowing what I would find, sometimes not even sure what I was looking for. Why was I so determined to discover or retrieve these fragments and fading documents of my family’s past? I had no answer other than the search continued to fascinate me, to broaden my perspective and understanding of history and humanity. The story of a family is the story of so much more.

Perhaps the simplest and best answer could be found in the haunting question posed by the main character in W.G. Sebald’s novel, Austerlitz. “And might it not be,” he asks, “that we also have appointments to keep in the past, in what has gone before and is for the most part extinguished, and must go there in search of places and people who have some connection with us on the other side of time, so to speak?”

Yes. As the Grey Folder had reminded me, I had many appointments to keep in the past.

NOTE: The Grey Folder Project is not a family genealogy, but rather a narrative of my search and discoveries. As such is designed to be read consecutively, with links within each "chapter" that show documents, give background and/or expand on the subject. As this is a work in progress, I will continue to add to the web site. An index to the main pages (or "chapters") and background pages of the site can be found through a link at the bottom of every page.

GIVING CREDIT: The letters, pictures, documents and written materials on this site, unless otherwise noted, are the sole property of Toby Sonneman. If you share any of these materials, please give credit to me as the author/owner and link back to this website. Thank you.

PLEASE contact me with comments or questions here.