THE GREY FOLDER PROJECT

Destination unknown

"I TRIED TO HELP RESCUE HER by asking the State Department for a visa, and I had even a hearing in Washington," my father said. "But the State Department officials said, 'Why is she in Gurs? She sure must be a Communist.' They said that Mrs. Berger was apparently a Communist because the Germans had taken her to Gurs.

"Well, here was an old lady who had never been active politically. She had done nothing but sell sewing machines, and they could have very well given her the visa," my father told me. It was the only time I ever heard him criticize the government of his beloved adopted country. "I was the guarantor and so was my brother and so were the Lovemans in the back, but it did no good. Whatever I said made no impression. The State Department would not work together with us."

"And shortly afterwards, the Quakers informed us that she had been sent to Auschwitz."

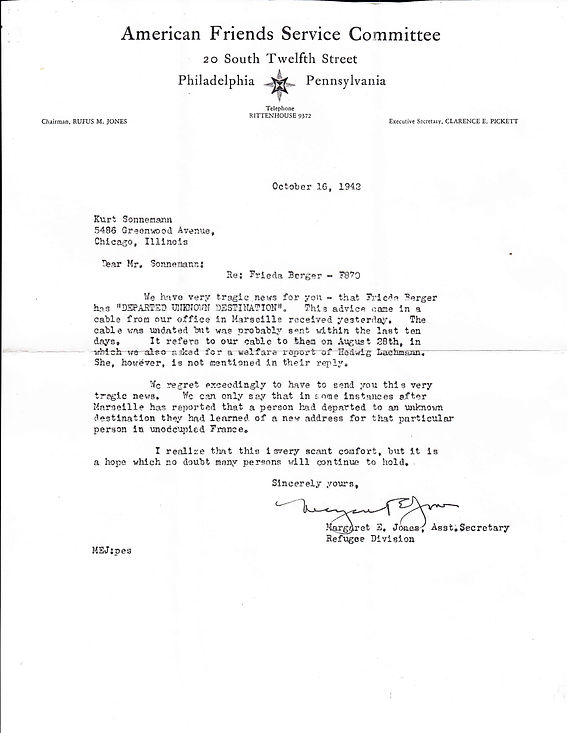

Actually what the Quakers had written was "unknown destination," but even in 1942 and especially accompanied by the words "very tragic news," the tone was ominous.

Re: Frieda Berger -- F870

We have very tragic news for you -- that Frieda Berger has "DEPARTED UNKNOWN DESTINATION."

THE LETTER WAS SHOCKING. It gave me chills every time I read it.

And I had read it often. For long before I discovered the grey folder, my father had shown it to me and given me a copy. And told me the story.

Now, though, I somehow had to find out more. I went to the university library to look at Serge Klarsfeld’s incredible work of documentation, Le Memorial de la Deportation des Juifs de France or Memorial to the Jews Deported from France 1942-1944, which lists all 76,000 names of Jews deported to Eastern Europe or killed in France.

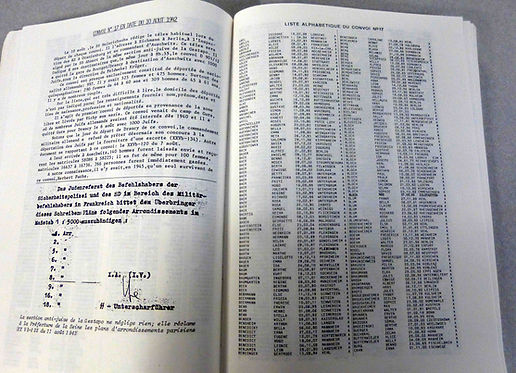

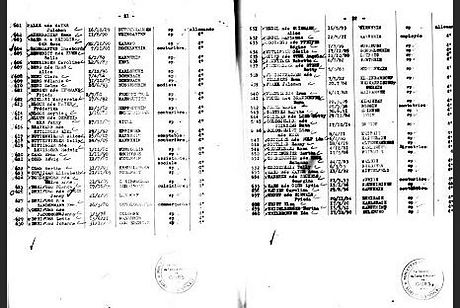

THE NAMES of the victims are listed in alphabetical order, for each of the 80 convoys, pages and pages in the oversize book, with row after row of names. It is startling in its blunt factuality. In the list for Convoy 17, I find Frieda Berger's name, one of 1,000 names of Jews, nearly all German citizens. Convoy 17 left Drancy, the concentration camp near Paris, on August 10, 1942, and reached its destination two days later: Auschwitz.

"This was the first convoy of deportees from the free zone, who had been turned over to the Nazis by the Vichy authorities,” Klarsfeld writes.

"Most of the first to be expelled were the same German Jews who had been deported from Baden to France in October 1940," writes Susan Zuccotti in The Holocaust, the French and the Jews. "They had been shipped west, only to be turned around two years later and murdered in the east."

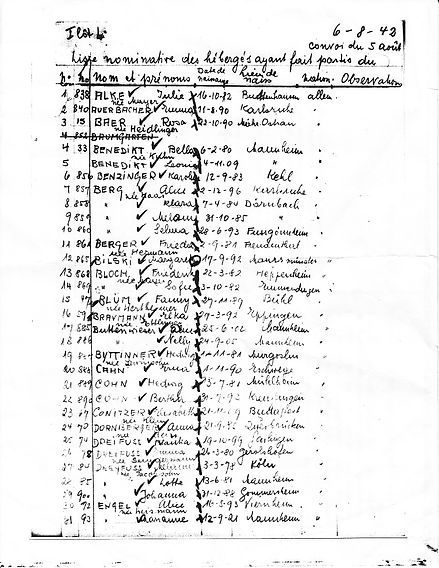

LATER, my research would turn up copies of the lists compiled by the Vichy officials in Gurs, for the expulsion order to Auschwitz. The list of names was read aloud in the camp to the silent, fearful prisoners. The order required all Jews with last names beginning with letters A-through-M to be packed into sealed boxcars and sent to Drancy on August 6, 1942.

Two days later, those with names beginning N-to-Z followed.

"BY DELIVERING THEM TO THE NAZIS as carelessly as they had handed over German political refugees the year before," Zuccotti writes, "Vichy officials in fact sentenced them to death."

"BEFORE DAWN, WHILE IT WAS STILL COMPLETELY DARK, police from the Garde Mobile surrounded the camps," writes Caroline Moorehead in "Village of Secrets." The welfare organizations, notified just days before that Vichy intended to hand over 10,000 foreign Jews to the Germans for deportation, had "a terrible moment of reckoning," Moorehead writes. "They had done everything they could to make life inside the camps more bearable, and in so doing had fallen into a trap: the camps had become 'reservoirs' for deportation."

"As it grew light in Gurs, the Jews with names beginning with the first 13 letters of the alphabet, A to M, were told to pack their cases. The others watched in silence as the frail, ragged inmates dragged their bags and their suitcases, held together with string, towards a designated hut... There were agonising scenes as people tried to kill themselves, swallowing anything they could get hold of. Others wept and struggled. . . When at last the first group was ready, it set off for the station, the infirm on crutches, the bedridden on stretchers." (Moorehead, Carolyn, Village of Secrets, p. 61-62)

IT WAS THE END FOR FRIEDA. My father told me that whenever he said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, he prayed for her.

But hearing this story, and looking at the incontrovertible facts, I couldn't let it rest. I felt there was something missing, something I had to continue looking for. And a question was eating away at me: Why couldn't Frieda have been saved?